VCAs, a vital piece of a touring professional’s tool kit… a mystery acronym to a weekend warrior.

VCAs, a vital piece of a touring professional’s tool kit… a mystery acronym to a weekend warrior.

VCAs aren’t new to mixing consoles, but they are still new to a lot of sound engineers making their plunge into the world of digital consoles. VCAs were introduced in the analogue mixer heyday on the very highest of high-end mixing consoles but only the more privileged engineers in those high-end venues could get their hands on them.

Now, thanks to modern tech, VCA’s are available on pretty much every digital mixing console; attainable price-wise to any budding engineer or venue.

Well VCA stands for Voltage Controlled Amplifier.

All I really know is that a VCA in analogue terms, is an electrical component that is placed on every input channel; this VCA replaces the traditional resistor-based fader where audio passes through depending on the resistance level. The audio amplifier section of a VCA is controlled by varying its DC current; the faders on VCA-ready consoles vary the DC voltage going into these VCAs. So with some clever switching, you can assign a bunch of these VCA components to a controller that collectively varies the DC current being fed to each of the contributing channels (my technical expertise is now exhausted).

So in short, a VCA system allows you to control the level of a bunch of input faders by using a single VCA group master fader. You could group all of your drum channels to a single fader so that turning the drums up or down can be done with one finger; no 8-finger stretch required. You could also group a bunch of Backing vocals or Choir mics into a VCA, or maybe all of your FX returns? The sky is the limit!

Of course, in digital land, this complex (and expensive!) portion of analogue electronics can be replaced with a bunch of 1’s and 0’s, and renamed DCA’s (Digitally Controlled Amplifiers), however the point remains, being able to control the balance of 128 channels with 8 or 16 faders is vital; why juggle all 128 balls when you could ‘simply’ juggle 16?

So, you may be wondering, well, that’s exactly the same as Subgroups! I know how they work; they do what they say on the tin, why should I bother with VCAs! Well, whilst the result is the same regardless of which tool you pick, there are various issues that you could encounter when using Subgroups that are eliminated with VCAs. That’s not to say that Subgroups don’t have their advantages and uses, however hopefully, after this article, you can see the benefit of both and with any luck, dust off that VCA section on your mixing console that you’ve been avoiding.

So we know what VCA’s were in analogue days and how they work. We established that the same functionality is now available in the digital world but also that subgroups kind of do the same thing! So, what’s the difference? When would you use either/or?

Subgroups come into their own when you need to send your grouped signals onto a new location (such as a set of subwoofers or satellite speakers). VCAs are just controls that alter DC current, no audio passes through them and they don’t sum audio or send it anywhere. The subgroup switches on each channel are a bit like closing-up a dam on several rivers so all of the water flows to a new destination, in this case, a set of stereo group faders and a dedicated Line Output. This audio can be sent back into the LR for a traditional subgroup operation (adjusting the drums level in FOH with one fader for example), however the complication arises in applications where the contributing channels are being sent to multiple outputs, internal busses or physical locations.Imagine you have a single vocal channel being routed to a subgroup fader and also a Post-fade Aux send to an FX engine. Raise or lower the group master fader and the dry signal into FOH will be adjusted but the wet effects channel will remain the same volume. Turn the group fader all the way down to -∞ and the dry signal is cut, but the wet signal is completely unchanged, still echoing it’s way around the venue’s PA – not ideal.

Replace this system with a VCA and when you raise or lower the VCA controller, it effectively raises or lowers the vocal channel level and thus affects the channel level to the group AND any post-fade sends proportionally. When you multiply this by 10 and over a whole group of choir mics that are being sent to two destinations (FX-post fade and LR bus) then a VCA controller will adjust the levels of both FX sends and channel levels in proportion with one another… all with one fader.

This sounds complicated, but the VCAs are essentially turning the contributing faders up and down in proportion to one another and so anything that is being fed post-fade by those channels is also having its send level affected. The subgroups are just receiving the signal elsewhere down-stream, they cannot adjust the individual flood gates to new locations, just the overall volume… I guess they just aren’t very intelligent!

The wonderful thing about the VCA is that you could also assign input channels to several VCAs! Why not create Drums, Bass, Strings, Bvox, Vox, FX & Band VCAs that contain all band instruments in one VCA. If you’re in the show and you need to make more space for your vocals (if you want to be really lazy) just turn down the band VCA – saves reaching for those other VCA masters! (economy of motion is key in live sound).

Why stop with input channels! You could assign all of the FX send busses to a VCA, or maybe all of your aux bus masters? Or maybe, several subgroups!?

High-end digital consoles allow anything to be assigned to VCAs… even other VCAs!

An advantage of course with Subgroups and the large mass of signal that is sent to the group busses is that you can apply a compressor or an EQ across a whole subgroup to glue together those drums for example, or EQ out the harshness in those BV’s . All with just one move on the instrument group and not on each individual channel.

That’s not to say that VCA’s cannot operate in a similar way of way of course…

When you move up the digital console levels towards high-end broadcast systems, VCAs can take on new responsibilities and with it, more advanced possibilities.

In digital land, VCA’s aren’t component related at all! It’s just ones, zeros, adds and subtracts… (before all coders begin to throw their laptops at me) it is of course a lot more complicated than it seems, however it does mean that with no extra circuitry or advanced bounds in analogue technology, a bunch of very talented programmers can take VCAs to the next level; meet the CGM (control group master).

If you can control a bunch of input fader levels in proportion to one another digitally via an external fader, why stop there? CGM’s provide the VCA master fader with a Pan, EQ and Dynamics processor that can work across all of the assigned contributing channels. If you have all of your drums assigned to a VCA and feel like you need to reduce the high end by 3db, you could reach for the EQ on the CGM, and reduce the high-end by 3db. This control then offsets each contributing drum channel EQ by 3db. If your kick drum had a broad boost at 4khz by +9db, it will now be at +6db, and that boxy cut at 400hz by -4db is now at -7db (3db lower).

These GCM’s are a fantastic tool for treating a group of channels under one ‘channel strip’. Whilst the compressors don’t quite ‘glue’ things together in the same way as a bus compressor would across a subgroup, you can a least squash everything just a little bit more without A) ruining all of your settings on each contributing channel and B) without getting RSI adjusting each channel individually…

The one thing you have to be careful of with this is that your offsets cannot be retained if you are at the extremities of your processing. I.e, if (for some reason) you are cutting a frequency by -15db on one channel (the maximum for your console) and 3db on the second channel, turning the EQ on your GCM by -10db will result in channel one being unchanged (at -15db) and channel 2 now resting at -13db, only a 2db offset from the previous 12db. Obviously, if you are cutting anything by that much then you probably have a more serious problem elsewhere in your chain, however it is something to be aware of…

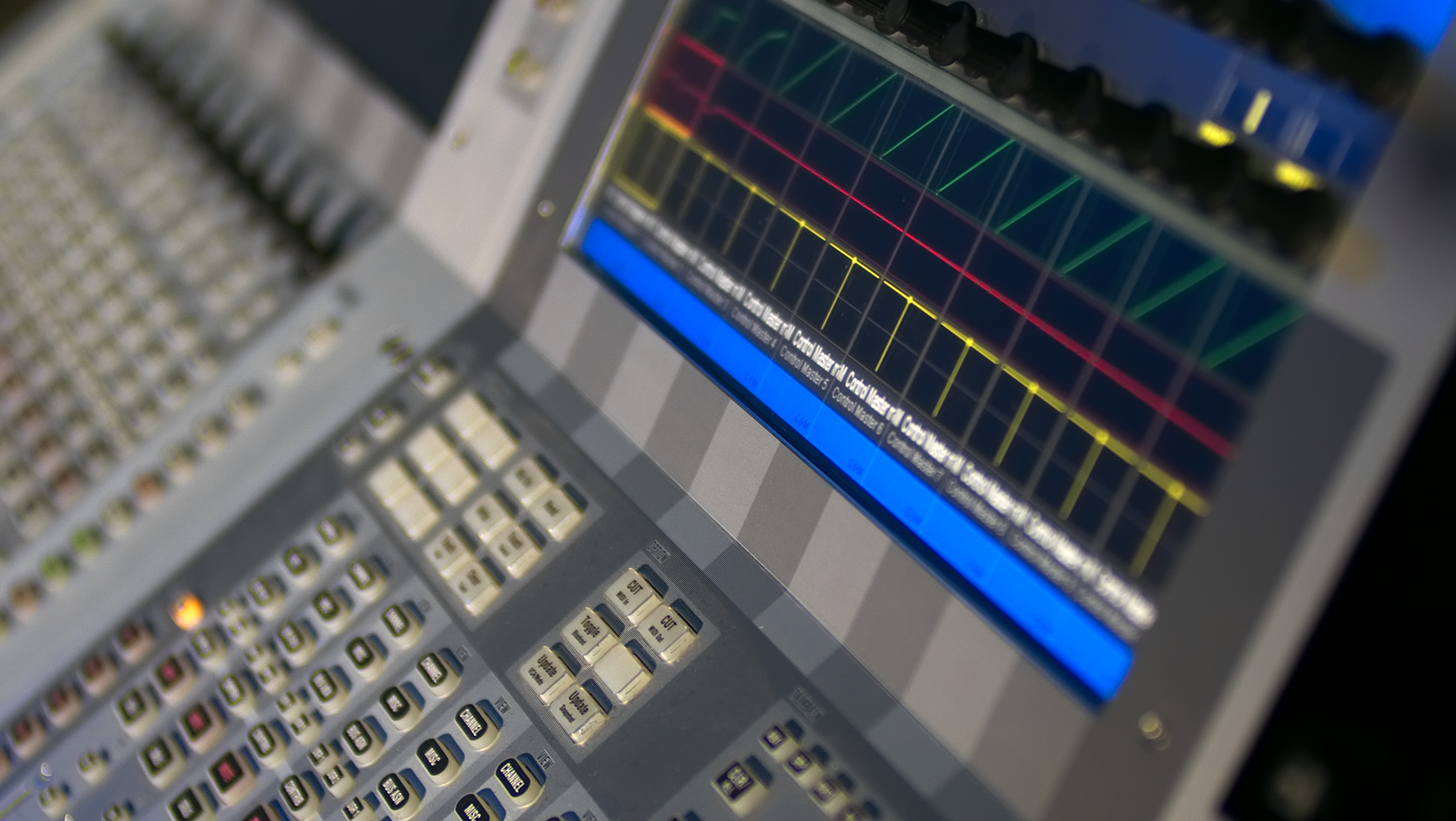

Some consoles such as the Studer Vista broadcast console allow for even more options to be linked within a control group such as Aux sends, input settings, and bus routing. This really pushes the boundaries of our lowly VCA and moves onto something a little bit different (and moving up to big-bucks consoles!).

So you may think we’ve reached the very end of our VCA explorations… but no… there’s more. Aux VCAs…. VCA spill…. And the future that is yet to be written – how exciting!

So what started off as a mystery object has turned into a pretty impressive tool for mixing your show. We’ve spoken about what VCAs are, where to use them and also how they have evolved into GCM’s… but there’s more! The VCA has entered greater heights in recent times, improving not only the ability to mix tons of channels in FOH… but also aid the braver and far more under pressure monitor engineer (in my opinion!). Let’s talk about using VCAs for monitor mixing and ‘Aux VCAs’ in particular.

As the client gains popularity and their pockets get deeper… so does the size of their live production.

For you monitor engineers a part of this journey, you enter the realm of in-ear monitoring and bigger, more complex channel counts than you could ever imagine. This is only made more difficult by the fact that any musician could want a specific channel at a specific level for a specific moment of a specific song. It sounds a bit OTT, but you can’t exactly say ‘NO’ to Chris Martin – the man paying your bills.

To help combat this need for constantly adjusting the contributing levels to each monitor mix, our VCA controllers can take on a new guise when we are mixing to a monitor bus. Imagine you’re on something like a Soundcraft Vi7000; you have your 8 VCA masters in the master bay and you have input faders to the left and right. If you flipped the faders to mix into Aux 1, your input faders would flip (and display a new faderglow colour) but so would your VCA controllers. That’s because, when you are within a mix, you can use the VCA masters to adjust the levels of that VCA group within that selected aux. If your musician wants less drums in their in-ears, simply reach for the drum VCA whilst you’re in their mix and adjust the level. The VCA controller is not affecting the FOH bus or any other monitor bus, just the aux bus you are currently mixing to.

In Soundcraft’s case, they call these ‘Aux VCAs’ and the faderglow colour changes from Blue in FOH to White in Aux modes. Other manufacturers call it different things (MCA) and some have the functionality just on by default.

On higher end consoles, each VCA can have the ‘Aux VCA’ mode enabled or disabled by default. There are occasions where you would always want access to a standard VCA regardless of what mix you are in. Lead Vocals perhaps, or maybe FX returns so that you can turn those down in-between songs. In the monitor world, the mixture between standard and Aux VCAs is vital to running the show.

Remember when we spoke about how a VCA can adjust the FOH level as well as any post-fade channel send contributions to mix busses? Well, In large shows where the musicians are using in ear monitors, the production requires the monitor engineer to send audience and venue ambience mic signals into each monitor mix. This signal would then be faded up into each monitor mix in-between songs so that the musicians feel connected with the audience and receive all of the lovely praise that they feed on to perform their set.

It would be pretty hard work for the monitor engineer to adjust the levels of the ambience mics individually as there could be 8+ of them in some instances; also, it is very likely that the engineer might need to get to these ambience controls whilst they are knee-deep in a monitor mix; a few button presses away from the FOH layer.

A very common fix is to send these ambience mics to each monitor mix POST FADE and assign them to a VCA. Once this VCA has the ‘Aux mode’ turned OFF, then you can simply reach for the VCA master no matter what bus you are mixing to.

This also means that the engineer can ride the ambience levels to all of the musicians monitors for any ‘call and response’ during or between songs, being careful not to confuse the musicians with loud, out-of-time ambient signals.

Moving back to in front of stage, a more recent chapter to the VCA has been the evolution of VCA spill - the act of unfolding all of the VCA contributions onto the present surface for quick navigation of instrument groups. Simply engage VCA spill, select the VCA master and then all of the channels that are assigned to that VCA are then ‘spilled’ out on the mixer surface, all in consecutive order, side-by-side.

Many engineers mix the whole show by using this feature as it means minimal fader layer switching and a navigation system that displays only the things you need at any time on the surface within 1 button press. When you’re mixing upwards of 100 channels, this is vital.

Broadcast consoles have taken this to the next level where you can assign a group of faders to carry out your VCA spill duties. This ‘Spill zone’ is user defined to the whole surface or even just a single fader bay.

Some console manufactures have since adopted a system called ‘population groups’ or POP groups that essentially spill out contributions like VCA spill but are only attached to a button and not a conventional VCA.

So what’s next for the VCA! They’ve come a long way as you can see and there’s always a time where improvement seems impossible. VCAs can perform a multitude of tasks from menially turning a bunch of channels up and down to organically mixing and adjusting hundreds of bus sends and mix levels all with one push of a fader.

Personally, I see a future where you could use a VCA group to build your aux mix, where you flip your console to mix into Mix 1 and all of your predetermined VCA groups are at -∞. When you want to turn up the drums, you just raise the drum VCA and the contributing faders are raised in the same proportions that you have just set to the LR. You at least get a starting point and somewhere to go after that. Hey, maybe even 90% of the time that mix would be okay, it would certainly save some time when you initially start building up them mixes.

There could even be a case to make VCAs more granular, maybe being able to create new VCAs whilst you’re within a monitor mix? - the value of which at this time I find difficult to see… but something I can certainly see people liking the look of.

Regardless of how you use VCAs or if you’re convinced by what I’ve said, I hope you found this useful! Dust off that VCA section and give them a go next time you’re out, you might like’em!

This new blog is presented by the team at Sound Technology Ltd, a leading distributor of musical instruments and pro audio equipment in the UK and ROI.